Lying in our comfy bed in the Capital Inn in Juneau AK, I could hear the big cruise ships blowing their fog horns throughout the night. Normally I like the sounds of the sea, but as I went in and out of sleep I was vaguely aware that heavy fog was not a good thing tonight. We were scheduled to leave at 8 am for a helicopter ride to the Mendenhall Glacier. Our first attempt, the day before, had been cancelled due to the foggy and rainy weather. We got up early and packed our bags just in case, but it was like pea soup looking into town from our window. At 7:58 the tour company called to cancel. I knew they had a 9:00 departure and asked if we could join that one. A long shot, but maybe in an hour the fog would lift? We weren’t optimistic, but it seemed worth a try.

The only good thing about the cancellation was that we were able to join the big breakfast at the Capital Inn. All of the inn’s guests gathered at the large dining room table for a multi-course feast of fruit, muffins, and steak-and-eggs (and lots of coffee). It was a jolly meal, but one of the guests was a Fed Ex pilot, who confirmed that the airport was closed right then and that it was no day for flying. After breakfast we went back to our room and puttered around, assuming that the 9:00 tour would be cancelled and wondering how we would spend the time until 4:00 pm when we had to board our cruise. By this point, we had seen most of what Juneau had to offer. The Alaska Art Museum, which was supposed to be pretty good, was closed for two years to be rebuilt. We’d already spent more time in the Alaskan Bar than was strictly necessary. So the hours ahead loomed large.

We were utterly startled when Linda, the host of the hotel, knocked at our door promptly at 9:00 and reported that a van was there to pick us up. This couldn’t be right, because the visibility in Juneau was only about half a city block. But there the van was, so we scrambled to pull ourselves together, left our luggage in the downstairs hallway, and hopped in the van – immediately lamenting the stuff we forgot (like gloves). We were going to a glacier, after all, and it probably would be cold.

The van picked up a group from a cruise ship and headed toward the airport. I confess that I was feeling considerable anxiety. I should mention here that while I travel a fair amount, I really don’t like flying at all. It’s that whole “taking off” and “landing” thing that gets me; if we could just skip those parts it would be great, because I’m fine in between. And I had never been in a helicopter before. Suddenly, on the way to the Juneau Airport, experiencing my first helicopter ride in thick fog seemed like an extremely bad idea.

At the airport we were ushered into the gear room for the tour company, NorthStar Trekking (www.northstartrekking.com), where we put on their gear, leaving ours behind in lockers. We all wore the same orange jacket, black hiking pants, utility belt, helmet, gloves (no need to worry about the ones we forgot), and hiking boots. Weeks earlier we had provided our shoe sizes and weights (the latter to my dismay…but do you really want to lie about your weight when it might cause the helicopter to go down? I don’t think so). Because the company had this information in advance, each person’s gear was labeled and waiting for him or her. We got instructions on the gear and on helicopter safety from the NorthStar crew. They seemed to know what they were doing, but each of them looked about 16. Please tell me these aren’t the helicopter pilots, I said to myself. Should I raise my hand and ask?

My stress level escalated as one of the 16-year olds escorted us to a waiting helicopter and strapped us in. This kid is considerably younger than my youngest child, I thought, and my youngest child — though I love him dearly — would not be able to land a disabled (or even a perfectly functioning) helicopter in the mountains, even if he had been training for that very moment his entire 19 years. When we were all set to go – to my huge relief – a fellow who had to be in his late 30’s or early 40’s came bounding out and jumped into the pilot’s seat. He wore Ray-Bans and a well-trimmed beard and looked like my vision of what a back-country helicopter pilot should look like. OK, I’m good to go.

I was seated next to the door. Aside from my recurring visions that the helicopter door would fly open because the teenager hadn’t secured it, leaving me dangling out the side while the passenger sitting next to me tried to yank me back in, the helicopter ride was spectacular. The door didn’t pop open, and I didn’t fall out. The lowest of the clouds had lifted, and while it was not exactly sunny, it was clear enough to appreciate the view.

We flew over the Mendenhall Glacier, which we had only glimpsed the day before from our hike.

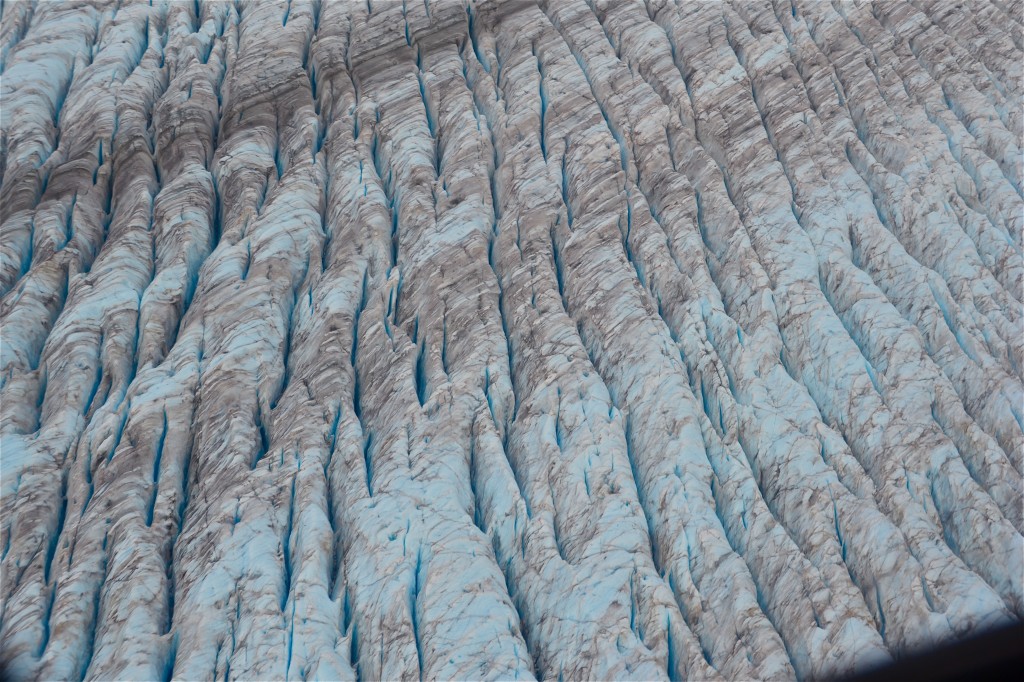

I will confess that I really didn’t have a clear idea of what a glacier was until I got to Alaska. Now I’ve seen a lot of glaciers and have a primitive understanding of them. For those of you who are glacier novices, glaciers start from huge icefields like the one pictured below — a tiny corner of which we flew over:

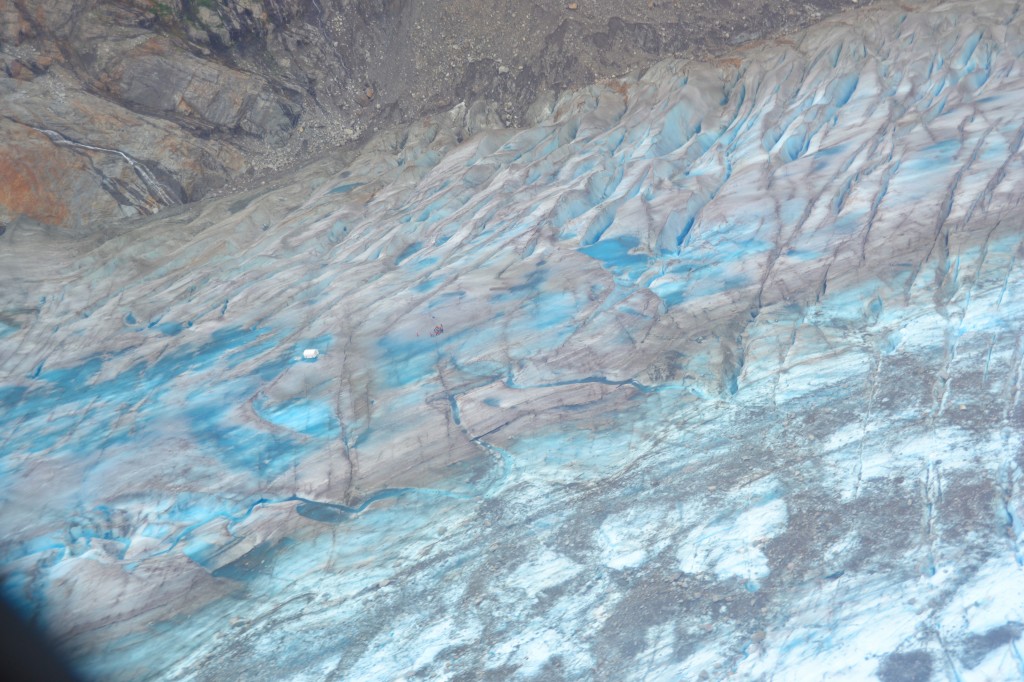

The Juneau Icefield is 1500 square miles of snow, way up high. Year after year of snowfall compacts the snow into ice, forcing rivers of ice to spill over the sides, down the mountains, often toward the sea. The glaciers are moving bodies of ice. As they move along, they carve out the stone that they pass through and over (which may result in spectacular fjords a few hundred years later). One of our guides said that a woman (probably from my adopted home state of New Jersey, because it sounds like something a Jersey girl would ask) asked him, “Why don’t you clean your glacier? It’s so dirty.” (“Why dontcha clean yuh glayshuh?”) The “dirt” is the glacial silt that the glacier picks up as it plows through the mountains. This is what it looks like from thousands of feet above:

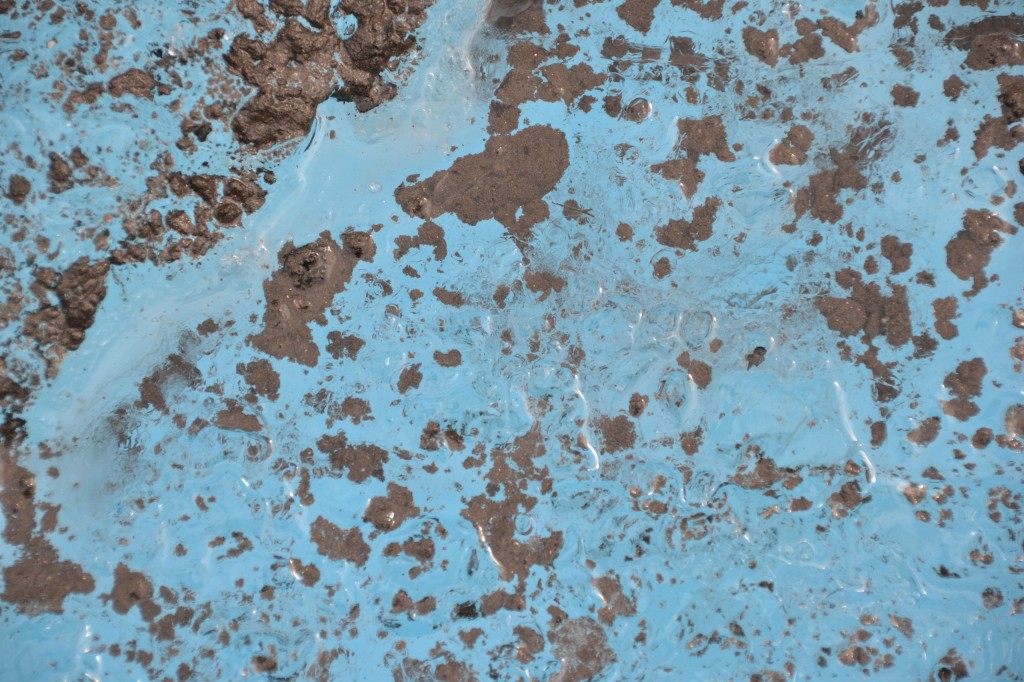

Below is what the glacial silt looks like up close, a foot away. They say the silt makes a great mask for your face. Perhaps, but I can report that we took a small sample of it for our collection of sand (and sand-ish things) from around the world, and when we got home and opened up the container, it smelled pretty nasty. Not sure I’d want to slather this stuff on my face. It’s possible that I’m becoming a Jersey girl, after all these years of living here.

The helicopter pilot threw in some drama…banking up against some cliffs, while pointing out that we were moving at a speed of about 160 mph. Maybe it’s hard to appreciate the photo below, but we were rather close to some large pieces of ice. When I turned around to look at Dave, he was smiling but looking a little green in skin color.

Next the pilot flew back out over the glacier itself, heading toward our destination – an orange dot. From above the glacier, it’s very difficult to get a perspective on its size. I figured the dot was a small buoy that had been left as a marker. Can you see it in the lower left of this photo? Probably not; it’s really tiny and I’m not pleased with the reproduction of my photos on this blog. My photos were pretty good, if I do say so myself, especially considering my state of mild terror; it’s the internet that sucks.

In the photo below the dot is getting much closer and bigger, because we are about to land. You can see it in the center of the window.

And now we have landed. The orange dot turns out to be a 10-person tent. I suppose that if the weather had turned bad, we would have spent the night in that tent. That wasn’t a great thought, as there were more than 10 of us…not to mention the fact that we were supposed to board our cruise that very afternoon. Luckily, that didn’t happen. In fact, the weather was the best we had seen since our arrival in Alaska two days earlier.

The two helicopters took off, leaving us alone on the glacier.

We met our two guides and were helped into crampons (the spiky things that attach to your hiking boots). Each of us was given a substantial ice pick as well, making each of us just a little bit dangerous. Who knew what the sprightly 70-year old matron from Haddonfield would do when armed? We briefly practiced walking up and downhill. The Haddonfield lady struggled a bit, and I helped her up after a stumble. She seemed unlikely to wreak havoc with her icepick, at least not on purpose. (But what about that husband of mine? Could this be part of some grand plan of his to get rid of me? Note to my children: if I ever happen to be found at the bottom of a crevasse at a glacier, with icepick wounds, it wasn’t an accident.)

Each of us was given a substantial ice pick as well, making each of us just a little bit dangerous. Who knew what the sprightly 70-year old matron from Haddonfield would do when armed? We briefly practiced walking up and downhill. The Haddonfield lady struggled a bit, and I helped her up after a stumble. She seemed unlikely to wreak havoc with her icepick, at least not on purpose. (But what about that husband of mine? Could this be part of some grand plan of his to get rid of me? Note to my children: if I ever happen to be found at the bottom of a crevasse at a glacier, with icepick wounds, it wasn’t an accident.)

The crampons were pretty easy to master, especially for people like us who are used to walking around in clunky ski boots.

We spent the next two hours hiking around on the glacier. It was, without question, one of the coolest things I’ve ever done. This might be a good place to say THANKS to Melanie Tucker at Tough Love Travel for arranging this trip. Most of these photos speak for themselves.

Dave tried to go off on his own a few times, which gave the guides agita. The problem with wandering off is that the ice is moving all the time, and crevasses may form that were not there the day before. So the guides tend to be very wary, as they should be.

There were streams running throughout the glacier, sometimes at odd angles.

You could walk through water in the boots, but you had to be careful because some of the pools got very deep.

We saw some people learning how to ice climb. Honestly, the setting was so spectacular that I don’t think I would have liked spending all my time in just one spot on the glacier, as these folks were doing.

We brought our son’s GoPro on this trip, and today was the first day we tried to use it. Our attempts to film led to a bunch of still photos along the lines of this:

Once we got the hang of it the GoPro was easy, but we definitely did not have the hang of it on the glacier.

Once we got the hang of it the GoPro was easy, but we definitely did not have the hang of it on the glacier.

After a few hours we took off our crampons, just as the helicopters came back (this was no accident; the guides were in radio contact with the pilots). The photo below is kind of interesting to give perspective. You can see the white tent of a competing tour company with the cluster of little ant-like people to the right of it. This was far, far away, on the other side of the glacier. These glaciers are really big.

Below you can see the Visitors Center on the left and the hills above it, where we had been hiking in the pouring rain the day before. The Mendenhall Glacier is about as urban a glacier as you might find, given that it is only 15 miles from Juneau. It’s rapidly receding, and the prediction is that in 25 years or so you won’t be able to see the Mendenhall Glacier from the Mendenhall Glacier Visitors Center, which is kind of embarrassing from a planning perspective. Now that I have come to appreciate glaciers, I do lament their disappearance, but to be somewhat even-handed about this, most of them have been receding since well before the Industrial Age. They’re just receding at a much faster clip. After another stunning ride, we were back at the Juneau airport. We retrieved our own outdoor clothes, and the van returned us to Juneau, where we celebrated the adventure at Tracy’s King Crab Shack. Some Dungeness crab with the meat already picked out was a tasty appetizer, and we each got a King Crab leg to work on. Plus a bottle of white wine to split. Yum. (Except we couldn’t finish all the Dungeness crab so we brought it with us onto the cruise; after three days of sitting in our cabin it smelled a little less tasty.) Tracy’s has a pretty good business plan: Just serve people crab legs on a piece of paper on picnic tables. Charge a fair amount, because the crab is really good. Have folks go pick up their own wine from a separate wine trailer. Don’t bother with wait staff; just yell out the names as the orders are ready. Worked for them and for us.

After another stunning ride, we were back at the Juneau airport. We retrieved our own outdoor clothes, and the van returned us to Juneau, where we celebrated the adventure at Tracy’s King Crab Shack. Some Dungeness crab with the meat already picked out was a tasty appetizer, and we each got a King Crab leg to work on. Plus a bottle of white wine to split. Yum. (Except we couldn’t finish all the Dungeness crab so we brought it with us onto the cruise; after three days of sitting in our cabin it smelled a little less tasty.) Tracy’s has a pretty good business plan: Just serve people crab legs on a piece of paper on picnic tables. Charge a fair amount, because the crab is really good. Have folks go pick up their own wine from a separate wine trailer. Don’t bother with wait staff; just yell out the names as the orders are ready. Worked for them and for us.

Late that afternoon we boarded the Wilderness Adventurer, our small cruise ship, to begin the water part of our vacation. More on that next time. Below is Captain Ron as we pulled out of Juneau.